What does ISO 31030 say?

We’ve been assessing business travel risk management arrangements since ISO 31030 Travel Risk Management – Guidance for organizations was introduced in 2021. In our experience, some organisations appear unsure about whether they have a duty of care for employees in their downtime during a business trip, or after the business element of the trip is complete but before the employee returns to their usual country location – the familiar scenario of ‘staying on a for a few days to do some sightseeing.’

A useful starting point for any discussion is to understand what ISO 31030 says:

‘Top management should establish a TRM policy that:

— sets out the organization’s policy with respect to off-duty time and personal leave time (both sometimes referred to as “bleisure”) associated with any travel,’

and

‘The organization should create an implementation plan. This should be approved by top management and should integrate the TRM function within the organization’s operations. It would commonly include the following…‘

Clarification of how risks arising during off-duty time or personal leave time (both sometimes referred to as “bleisure”) are to be managed/covered, if at all, by the organization’s travel risk processes.’

So, it is clear that ISO 31030 expects employers to develop a policy that addresses bleisure. However, the use of the words ‘if at all’ suggests that an employer does not necessarily have to adopt a policy position where responsibility is accepted for off-duty or personal leave time risks. It is possible therefore that an employer could contemplate a policy which holds that ‘we do not accept any duty of care responsibilities for any risks to our employees arising during off-duty time or personal leave time, in either case associated with business travel.’ But would such a position be defensible?

Some scenarios

Any answer to that question would have an ‘it depends’ element which is fact sensitive, so it is difficult to provide a blanket response that all off-duty/personal leave activity should be included in duty of care considerations, or none should be. Let us contrast the situation where an employee who is fit and is travelling for business in a country where they have lived all their life. They have made the journey many times before and are familiar with the area they are visiting. At the end of their business visit, they intend to stay with relatives locally before returning to their normal place of work in another part of the country. The worker will be claiming travel, hotel and subsistence expenses for the business portion of their trip but not for the stay with relatives. Arguably, it is likely that some employers would not regard any issue that arises during off-duty time or personal leave time in this scenario would engage their duty of care.

Contrast those circumstances with when the same employee is travelling to a country where they do not reside, may not have visited before, may not speak the local language, have no network of family or friends there, no familiar accommodation, and only have access to public transport. The geography, weather, politics, and cultural norms of the area are largely unknown to them, as are crime problems and whether their personal or protected characteristics may be relevant to their safety and well-being. An employer would probably conclude that this traveller is more exposed to risk than in the other scenario, and that the employer should be taking steps to address identified risks. This relative susceptibility might include when the employee is travelling between their accommodation and their place(s) of work during the trip. It might also extend to when they go out after work to take exercise, have a meal, or to relax; activities that are quite normal during any day.

In the next scenario, our employee has more than an evening off. Their business week finishes on a Saturday and resumes on a Tuesday, and so they intend to explore more widely using local available transport and on foot, but returning to their hotel each evening. They are not entirely sure where they will go each day but have some ‘places of interest’ brochures for the local area. Other than their mobile phone, they have no means of contact and don’t intend to tell anyone where they are going as they are not entirely sure themselves. Again, it is likely that this weekend work break would be considered part of a normal work cycle, and the employer’s duty of care to the employee is engaged, provided that the employee is not planning to undertake unusual and risky activities like parachuting or scuba diving without a suitably experienced local diver. Sometimes, insurance exclusions provide a helpful (though not wholly determinant) indicator of duty of care parameters.

The third scenario is where the business trip has ended, and the traveller has been granted x personal leave days which they intend to use for travel within the country (where business was transacted) and into an adjacent country by air. Because the return flight ticket for their home location was purchased by their employer, they propose to fly back from the location where they were working. They will meet all other expenses other than the return flight. In these circumstances, there are likely to be differences of view about whether an employer has a duty of care towards employees where the only obvious nexus between work and the personal break is the flight ticket purchased by the employer. Yet, some organisations do believe a duty of care exists because the flight home would have been paid for anyway, there is custom and practice of other employees having been granted the same facility of adding personal travel to business travel, the employer’s insurance policy provides cover in these circumstances, and the organisation would arrange assistance like evacuation for the employee should it be required, or the employer just thinks that it is the right thing to do.

Implications of assuming (some) responsibility for bleisure

But if organisations are, de facto, accepting a duty of care during personal breaks, one should then expect to see relevant elements of duty of care practice put in place including risk assessment, mitigation, contingency, employee briefing, and the means to maintain communication with the employee during their ‘break’. Suddenly, this may feel like the business is intruding int the employee’s private time. However, these steps are the logical consequence of employers assuming duty of care responsibilities for employees in personal leave time pursuant to business travel.

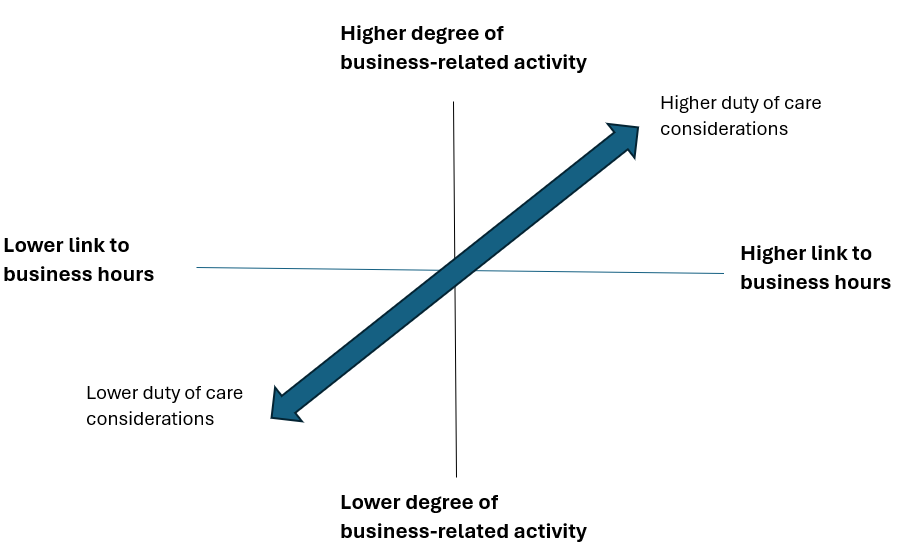

GSA Global has yet to identify any case law which is definitive but there are numerous cases where, sadly, ‘tourists’ have been killed on leisure activities and their families have sued widely. Also, we point to research data about the higher involvement of tourists in road traffic collisions, drownings and as homicide victims compared to host populations of countries visited1. The point is that tourism (substitute ‘bleisure’ for that term) often involves higher risks of serious harm and so the decision to assume a duty of care, or not, is often highly pertinent. It follows that it should not be treated as a grey area but one requiring balanced consideration and articulation. For example:

Conclusion

That employers have duty of care responsibilities for their employees during business travel off-duty time does not seem controversial. Wittingly or unwittingly assuming duty of care responsibility after the business travel has formally ceased raises implications for the traveller and the employer. Given the risks and liabilities of doing so, this is not a policy issue to be left to fester over time because un-thinking routine that ‘looks’ like duty of care activity can become a precedent. For these reasons, GSA Global advises organisations to think carefully about their approach to bleisure and to establish a policy position that demonstrates duty of care is understood and the circumstances in which it applies and, for the avoidance of doubt, when it does not. Travel is often an attractive aspect of people’s engagement with their company/organisation, and so it is imperative that the organisation’s policy is communicated clearly to those likely to be affected. We regularly raise this grey area because employers sometimes leave themselves and their employees exposed because of lack of clarity.

Finally, if you thought this issue is complicated, think about what duty of care is owed to business travellers who are contractors managed in one organisation whilst employed by another. But perhaps that is a conversation for another day…

Dr Brian Moore leads for TRM at GSA Global. The opinion expressed is not legal advice.